Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific breakthroughs and more.

CNN

—

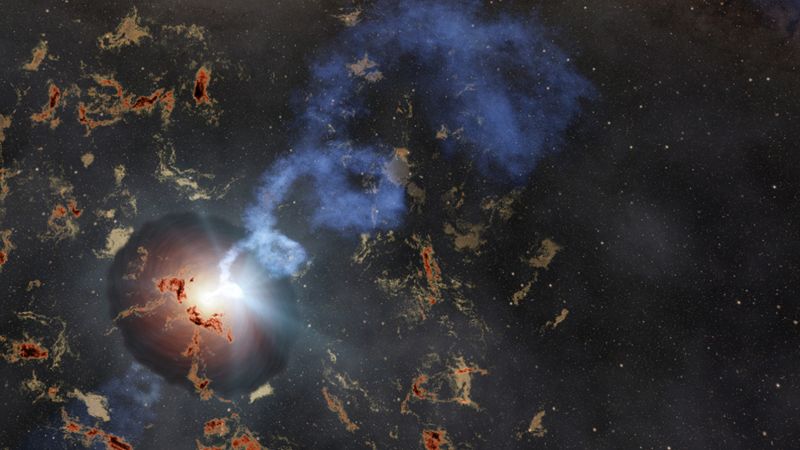

Space is full of extreme phenomena, but the “Tasmanian Devil” may be one of the strangest and rarest cosmic phenomena ever observed.

Months after astronomers witnessed the explosion of a distant star, they saw something they’d never seen before: vibrant signs of life from a stellar corpse about 1 billion light-years from Earth. Short, bright flares are almost as powerful as the original event that caused the star’s death.

Astronomers have dubbed the object the “Tasmanian Devil” and have observed repeated outbursts following its initial detection in September 2022.

But the initial stellar explosion that causes the star’s death is not a typical supernova, an increasingly bright star that explodes and ejects most of its mass before dying. Instead, it’s a rare type of burst called a flashing-fast blue optical transient, or LFBOT.

LFBOTs shine brightly in blue light, reaching their peak brightness and fading within days, whereas supernovae can take weeks or months to fade. The The first LFBOT was discovered in 2018And astronomers try to determine the cause of rare cataclysmic events.

But the Tasmanian devil raises more questions than answers with its unexpected behavior.

Although LFBOTs are unusual phenomena, the Tasmanian Devil is even more strange, causing astronomers to question the processes of repeated eruptions.

“Surprisingly, instead of fading steadily as one might expect, the source briefly brightens again and again — over and over again,” said lead study author Anna YQ Ho, assistant professor of astronomy in Cornell University’s College of Arts and Sciences. “LFBOTs are already kind of a weird, exotic phenomenon, so this is even weirder.”

Findings about the latest Tasmanian devil LFBOT discovery, officially named AT2022tsd, observed by 15 telescopes around the world, were published in the journal Wednesday. Nature.

“(LFBOTs) emit more energy than an entire galaxy of hundreds of billions of Sun-like stars. The mechanism behind this massive amount of energy is currently unknown,” said Jeff Cook, a professor at Australia’s Swinburne University of Technology and ARC Center of Excellence for Gravitational Wave Detection. , after the initial explosion and fading, intense explosions continued to occur, very rapidly—in minutes, weeks to months, like supernovae.”

The software Ho wrote initially flagged the event. The software sifts through half a million transients detected daily by the Swicky Transient Facility in California, which surveys the night sky. Ho and his collaborators at various institutions continued to monitor the outbreak as it faded, reviewing the observations months later. The images showed extremely bright spikes of light that quickly disappeared.

“No one knows what to say,” Ho said. “We’ve never seen anything like this before – something so fast, and as strong a glow as the original explosion many months later – in any supernova or FBOT (Fast Blue Optical Transient).

We have never seen that period in astronomy.

To better understand the rapid luminosity changes occurring in the Tasmanian devil, Ho and his colleagues reached out to other researchers to compare observations from multiple telescopes.

Jason Koski/Cornell University

Anna Ho developed software that detected signs of life burning from a stellar corpse.

In all, 15 observatories, including Ultraspec, a high-speed camera mounted on the 2.4-meter Thai National Telescope, observed 14 irregular flares in 120 days, a fraction of the total number of flares published by LFBOT, Ho. said.

Some flares last only tens of seconds, which astronomers suggest is a stellar remnant — a dense neutron star or black hole — formed by the initial explosion.

“This settles years of debate about what powers this type of explosion, and reveals an unusually direct method of studying the activity of stellar corpses,” Ho said.

Any object can pick up large amounts of material, fueling subsequent explosions.

“It pushes the limits of physics because of its intense energy production, but also because of short-lived bursts,” Cook said. “Light travels at a finite speed. So the size of a source is limited by how fast a source explodes and disappears, meaning that all of this energy is generated from a relatively small source.

If it’s a black hole, the celestial body ejects jets of material and propels them into space at the speed of light.

Another possibility is that the initial explosion was triggered by an unusual event, such as a merger with a black hole, which could provide “an entirely different channel for cosmic catastrophes,” Ho said.

Studying LFBOTs can reveal more about a star’s later life than just its life cycle, ending with explosion and remnant.

“Because the corpse isn’t just sitting there, it’s active and doing things that we can detect,” Ho said. “We think these flares could be coming from one of these newly formed corpses, giving us a way to study their properties as they form now.”

Astronomers will continue to study the skies to see how common LFBOTs are and to uncover their many secrets.

“This discovery teaches us more about the different ways stars end their lives and about the exotica that inhabit our universe,” said Vic Dillon, a professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Sheffield in the UK. A statement.