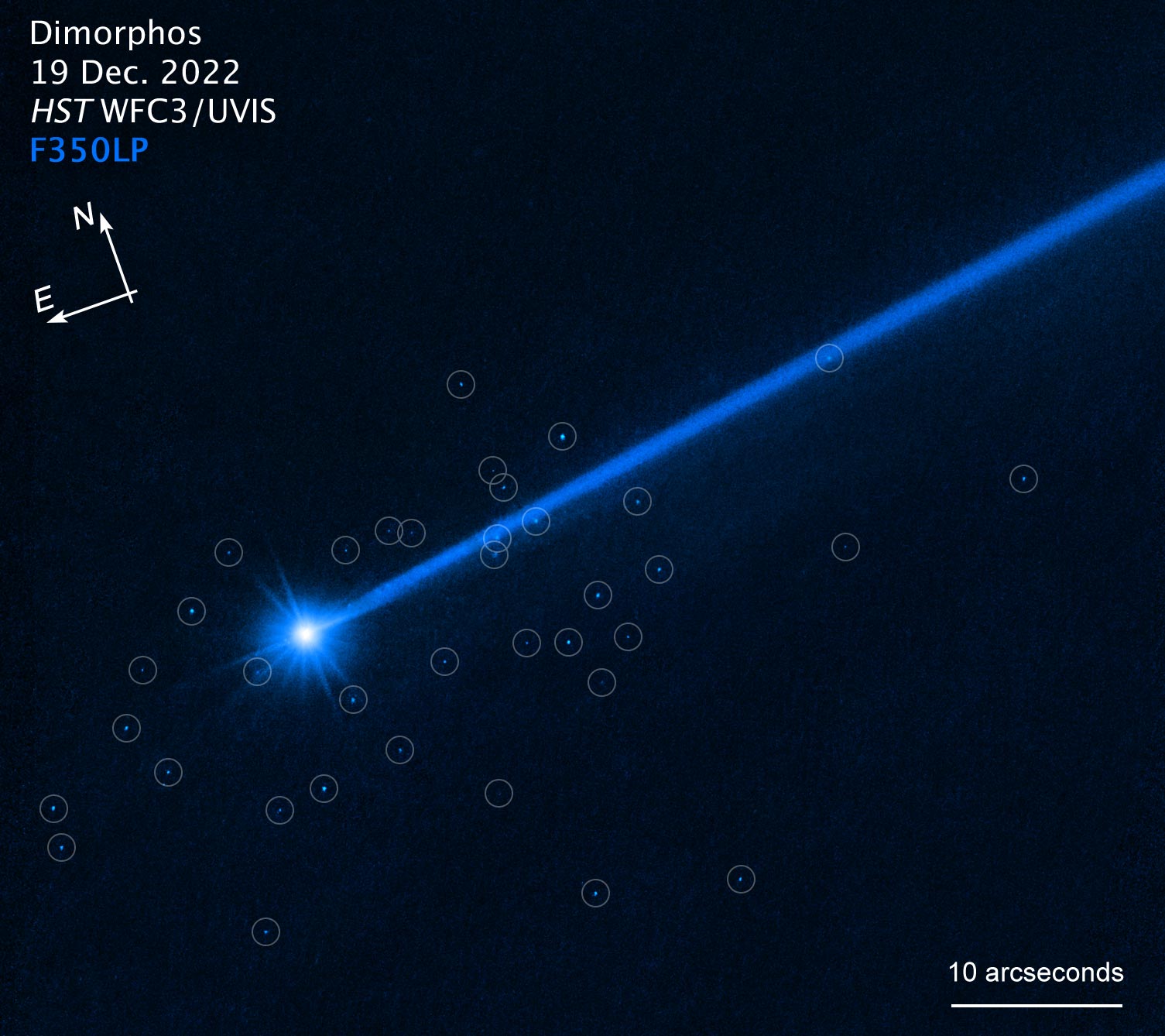

This Hubble Space Telescope image of the asteroid Dimorphos was taken on December 19, 2022, nearly four months after the asteroid was hit by NASA’s DART mission (Dual Asteroid Redirect Test). Hubble’s sensitivity reveals a few dozen boulders that were knocked off the asteroid by the force of the collision. These are among the faintest objects Hubble has ever photographed within the Solar System. Free-flying boulders range from three feet to 22 feet, based on Hubble photometry. They are moving away from the asteroid at about half a mile per hour. The discovery provides invaluable insights into the behavior of a small asteroid when it is hit by a projectile intended to alter its trajectory. Credit: NASA, ESA, David Jewitt (UCLA), Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

2022 DART mission impact hits asteroid’s surface

Sorry Chicken Little, the sky isn’t falling – at least not yet.

Wayward asteroids present a real collision hazard to Earth. Scientists estimate that an asteroid several miles across struck Earth 65 million years ago, wiping out the dinosaurs in a mass extinction, among other species. Humanity can avoid this fate if, unlike the dinosaurs, we start practicing how to knock back an asteroid approaching Earth.

It’s trickier than how it’s portrayed in sci-fi movies like Deep Impact. Planetary scientists first need to know how asteroids were assembled. Are they piles of loosely piled rock rubble or something more substantial? This information will help provide strategies on how to successfully deflect the threatening asteroid.

As a first step, NASA He did an experiment by crashing into an asteroid to see how it gets messed up. The impact of the DART (Dual Asteroid Redirect Test) spacecraft on the asteroid Dimorphos took place on September 26, 2022. Astronomers who use it Hubble Space Telescope Follow the aftermath of the cosmic conflict. One surprise was the discovery of dozens of boulders thrown from the asteroid. In Hubble images, they look like a swarm of bees moving very slowly away from the asteroid. If an asteroid smashes into Earth, it will send threatening boulders hurtling in our direction.

Image of asteroid Dimorphos with compass arrows, scale bar and color key for reference.

The north and east compass arrows show the orientation of the image in the sky. Note that the relationship between north and east in the sky (as viewed from below) is reversed compared to the directional arrows on a map of the ground (as viewed from above).

The bright white object in the lower left is a demorphose. It has a blue dust tail extending diagonally to the upper right. A cluster of blue dots (marked by white circles) surrounds the asteroid. These are the boulders knocked off the asteroid when NASA deliberately rammed the half-ton DART impactor into the asteroid on September 26, 2022, as a test of what to do to deflect a future asteroid from hitting Earth. Hubble photographed the slow-moving boulders using Wide Field Camera 3 in December 2022. Color is the result of assigning blue to a monochrome (grayscale) image.

Credit: NASA, ESA, David Jewitt (UCLA), Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

The popular 1954 rock song “Shake, Rattle and Roll” may have been the theme music for the Hubble Space Telescope’s recent discovery of what happens when asteroids demorph after NASA’s DART (Dual Asteroid Deflection Test) experiment. DART intentionally struck Dimorphos on September 26, 2022, slightly altering the path of its orbit around the large asteroid Didymos.

Astronomers using Hubble’s extraordinary sensitivity have discovered a mass of rocks shaken off the asteroid when NASA deliberately rammed the half-ton DART impactor spacecraft into Dimorphos at about 14,000 miles per hour.

Based on Hubble photometry, 37 free-standing boulders range in size from three feet to 22 feet. They’re moving away from the asteroid at about half a mile an hour—roughly the walking speed of a giant turtle. The total mass of these identified boulders is 0.1% of the mass of dimorphoses.

This is the last complete image of asteroid Dimorphos, as seen two seconds before impact by NASA’s DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) impactor spacecraft. Didymos Reconnaissance and the Asteroid Camera for Optical Navigation (DRACO) imager captured a 100-foot-wide swath of the asteroid. The DART spacecraft streamed these images to Earth in real time from its DRACO camera. DART successfully impacted its target on September 26, 2022. Credit: NASA, APL

“It’s a fascinating observation – much better than I expected. We see a cloud of rocks carrying mass and energy from the impact target. The numbers, sizes and shapes of the rocks are consistent with the impact from the surface of Dimorphos,” said David Jewitt of the University of California, Los Angeles. “This tells us for the first time what happens when you hit an asteroid and see massive amounts of material ejected. Boulders are some of the faintest things ever imaged inside our solar system.

Jewitt says this opens up a new dimension for studying the aftermath of the DART experiment European Space AgencyThe upcoming Hera spacecraft, which will arrive at the binary asteroid in late 2026. HERA will carry out a detailed post-impact survey of the targeted asteroid. “The boulder cloud will still be dispersing when Hera arrives,” Jewitt said. “It’s like a very slowly expanding beehive that eventually spreads out into the orbit of a binary pair around the Sun.”

This illustration depicts NASA’s Dual Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft before impact with the Didymos binary asteroid system. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Steve Gribben

Boulders are often not fragments of a small asteroid caused by an impact. They were already scattered across the asteroid’s surface, evident in the last close-up image taken by the DART spacecraft two seconds before impact, when it was only seven miles from the surface.

Jewitt estimates that the impact dislodged about two percent of the rocks on the asteroid’s surface. He says that Hubble’s observations of boulders give an estimate of the size of the DART impact crater. “Boulders may have been excavated from a circle about 160 feet across (the width of a football field) on the surface of Dimorphos,” he said. Hera will ultimately determine the actual crater size.

Dimorphos may have formed from material dumped into space long ago by the large asteroid Didymos. The parent body may have rotated too quickly or lost the object due to a collision with another object, among other scenarios. The ejected material formed a ring, which gravitationally coalesced to form a demorphose. This would result in a pile of flying debris of rocky debris held together by relatively weak gravity. Therefore, the interior is not solid, but has a texture similar to a bunch of grapes.

It’s not clear how the boulders were lifted off the asteroid’s surface. They may be part of the ejecta plume photographed by Hubble and other observatories. Or perhaps a seismic wave from the impact traveled through the asteroid — like striking a bell with a hammer — shaking and dislodging the surface debris.

“If we follow the boulders in future Hubble observations, we may have enough data to follow the precise paths of the boulders and then see in which direction they were launched from the surface,” Jewitt said.

The DART and LICIACube (Light Italian CubeSat for Imaging Meteorites) teams are examining the boulders detected in images taken by LICIACube’s LUKE (LICIACube Unit Key Explorer) camera in the minutes following DART’s motion impact.

The Hubble Space Telescope is an international collaborative project between NASA and ESA. NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland manages the telescope. The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland, hosts the Hubble and Webb science operations. STScI is operated for NASA by the Association of Universities for Astronomical Research in Washington, DC.